How to Estimate Agile Stories: Introducing Relative Sizing

by Todd Cotton, on Feb 10, 2020 11:36:33 AM

As an agile team, you want to avoid long, unpredictable planning cycles. You instead work in precise sprints or show work in progress on a Kanban board.

Though agile iterations are shorter and more adaptable, estimation is still the only way you can communicate to leadership when work will be delivered.

Over time, estimating enables us to know our team’s velocity so that we can accurately forecast work.

Estimate better, and faster, with relative sizing.

What do we estimate?

Agile teams estimate each user story and put that on the story card.

A user story is a short, simple description of a function needed by the customer. The story card displays one unit of delivery for the agile team, based on the user story.

For each story, we want to estimate its size.

To ensure we don’t slide back into traditional waterfall principles (where time is wasted on planning, and plans can’t adapt) we need a straightforward way to estimate.

If you’re new to agile estimating, your inclination is to think in terms of hours. This doesn’t work, however, because we’re rarely accurate when predicting in terms of time. It’s one reason we prefer short, iterative cycles to marathon planning sessions.

If story size is not about hours, how do we estimate? We estimate using relative sizing.

What is relative sizing?

Let’s think about the two parts of that term: Sizing and relative.

First, the size of a task or story is what must be estimated. It’s made up of three factors:

- Effort. How much work is required to complete this task?

- Complexity. How difficult or complicated is this task?

- Uncertainty. Do we know exactly what must be done to accomplish this task, or will we need to learn as we go?

The combination of these three factors is the story’s size.

Second, the size is relative to the other stories your team may have on its plate.

We find it’s easier and more effective to compare tasks and determine which is larger or smaller, rather than assign numbers or sizes to tasks independently without a reference point.

Introducing relative sizing with the fruit salad game.

If you’re new to relative sizing, we introduce the concept with a simple game.

Imagine you’re asked to bring a fruit salad to a party. You have one of several types of fruit—one apple, one cherry, one pineapple, etc. To make the fruit salad, each piece of fruit needs to be prepared. You’ll hopefully rinse each piece of fruit, and you may need to remove seeds, take out stems, and cut it into pieces.

During the activity, a volunteer is given one fruit at a time and asked to assign it a size. He or she must consider the effort, complexity, and uncertainty of preparing it for the fruit salad.

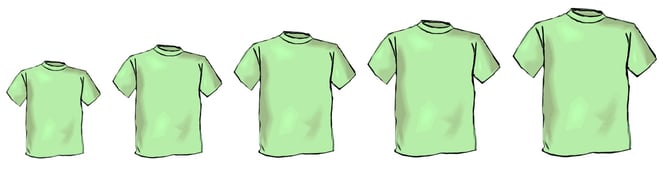

We typically start with T-shirt sizes written out across a whiteboard or wall:

You’re first given an apple. You’ll review the sizes and determine where it belongs. You may choose to label the apple a medium size because it takes a few minutes to remove the core and cut it up—but the task is not overly complicated.

-1.png?width=600&name=LD%20-%20Fruit%20Salad%20-%20Estimation%20and%20Sizing%201(kv)-1.png)

With the apple in place, you may next be handed a grape. You’ll decide, relative to the apple, how much larger or smaller the task is. Perhaps you decide it’s extra small because it’s easy to rinse and can be quickly pulled from the stem.

.png?width=600&name=LD%20-%20Fruit%20Salad%20-%20Estimation%20and%20Sizing%202(kv).png)

You’ll continue the exercise, considering the relative effort, complexity, and uncertainty involved with getting each fruit ready for your fruit salad.

.png?width=600&name=LD%20-%20Fruit%20Salad%20-%20Estimation%20and%20Sizing%203(kv).png)

After all fruits are sized, the team can debate the volunteer’s sizes. Adjustments can be made as new information and perspectives are presented.

Finally, the end result is a list of projects, each sized relative to the others in the salad.

How fruit salad translates to estimating real work.

With the concept now illustrated in bright and tasty colors, the conversation turns to how relative sizing applies to real work.

The first step is to determine what a medium project is. It’s the apple or pear in the fruit salad above.

Because sizing is relative, you need an anchor or gold standard story to compare all stories against.

Though it varies by team, we generally suggest the medium story is one that can be completed in a day or two.

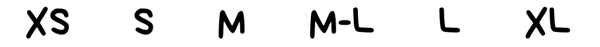

Apply the Fibonacci sequence to the T-shirt sizes.

Though not required, adding values to the T-shirt sizes used in the fruit salad game helps us estimate team velocity over time.

To do this, we use the Fibonacci sequence. Developed by the Italian mathematician, the sequence is created by adding the previous two numbers together (0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, etc.).

The value of using this sequence is that as story size increases, the gap between numbers widens. Massive projects are much harder to estimate to an exact number. The sequence keeps teams from getting hung up on minor differences.

-1.png?width=600&name=LD%20-%20Fruit%20Salad%20-%20Estimation%20and%20Sizing%205(kv)-1.png)

Learn how to determine your velocity with sizing and story points.

Over time, a team can use these estimates to project how many points of work they can complete per sprint (if using scrum), or during a defined timeframe.

Dive into story sizing and other agile techniques.

Agile is a system of values and principles. To turn those into action, teams implement various techniques and processes. The Agile Discussion Guide, in its fourth edition, is our team’s foundational playbook for agile transformation.